I am going to break a little from the narrative account and share some more “behind-the-scenes” of my research and approach. As I mentioned at the outset, my original goal of finding out about Grandpa Dan’s Silver Star morphed into telling the story of the 71st. I really wanted to ‘walk in his shoes’ and feel connected to what he must have gone through. One of the original visions I had was re-creating the 71st’s path across France, Germany and Austria by using maps. I’m a visual / spatial kind of person so seeing a place on a map makes it more real. What I’ve discovered now is going to take it to a whole different level.

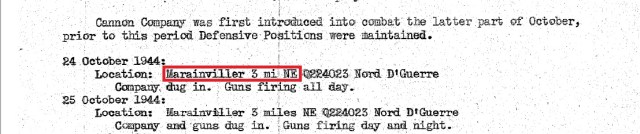

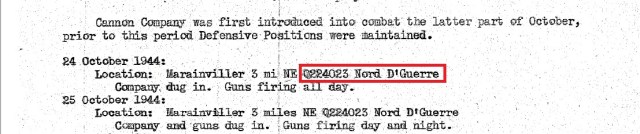

I obtained Operational Reports from the National Archives for the first few weeks of combat. I had hoped these reports would include specific locations for where the Division was. Sure enough, here’s an entry from the Cannon Company (artillery) for where they were located on the first day of actual combat:

What was most intriguing is this string of gobbledygook right after the mention of the town of Marainviller:

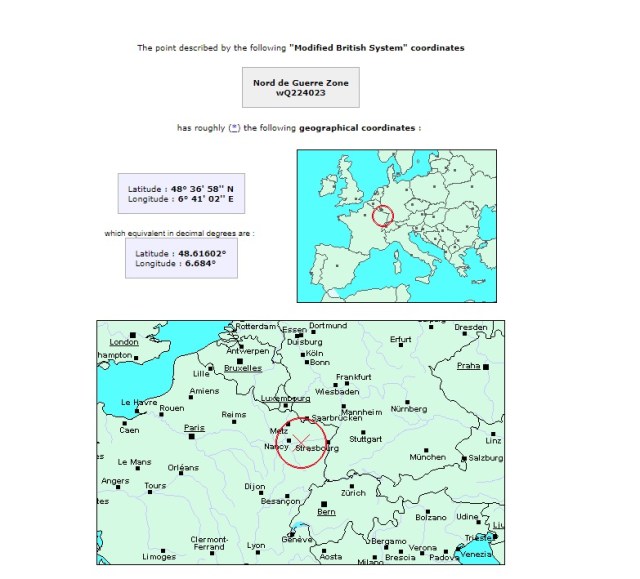

I don’t have military experience but I started to wonder if that string of letters and number was a map reference. Spending a little time with Google I started to wade into the system of continental maps that the Allies used in World War II. It was called the “Modified British System” and split the continent into large geographic areas and then further split those into a series of grid maps. More digging and I discovered a website that not only maintains the grids but can actually translate between the grid coordinates (like those in the S-3 above) to real Latitude and Longitude.

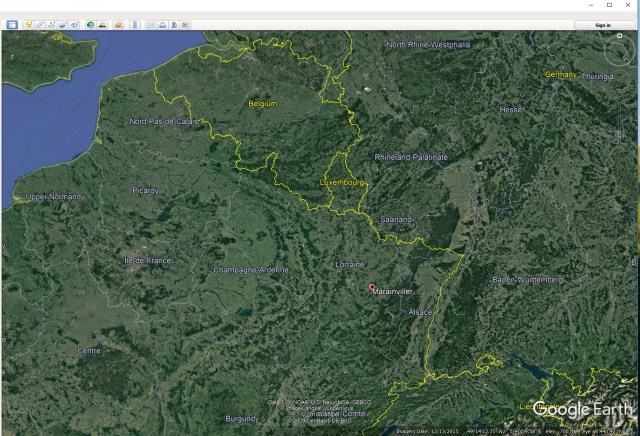

So, first step is figuring out which grid. I honestly had no idea so I pulled up Google Earth and did a search for “Marainviller”. Zooming out and turning on country borders I had this to study:

I went back to the map site and figured out that “Nord D’Guerre” in the S-3 report was telling me which big section to use. So, navigate to this page:

More studying and looking back-and-forth between the S-3, Google Earth, and this map and I had a “eureka” moment when I figured out the “Q” in the string of “Q224023” had to be the map “wQ” above.

I fumbled with the coordinate translator for a bit but finally it spit out this:

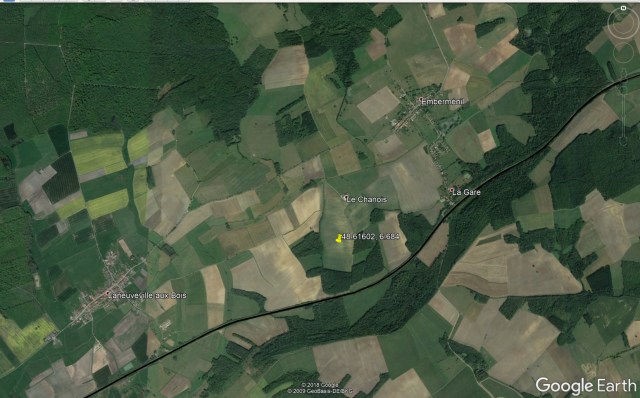

Holy crap. I’ve got the exact coordinates where the 71st Cannon Company was dug in on October 24th. What’s more fun is plugging those coordinates back into Google Earth:

Just for fun, I did a quick check on where the headquarters company was. They were in the ‘present bivouac area’ near Marainviller which was just south of the town and about 4.5 miles behind the cannon company:

What’s even more amazing is zooming into a street view and seeing what the countryside is like. Here’s a view just outside Marainviller on the road between HQ company and the Cannon Company:

I am absolutely blown away. I never thought I would be able to get this ‘real’ when it came to walking with my granddad. I plan to generously sprinkle these types of photos into the story I’m just starting to tell.

Up next is Dan’s travels from the Cotentin Peninsula to this part of France and the 71st’s entry into combat.

Each “hammock” was approximately two feet wide by six feet long, and was strung about two feet from the “hammock” above. These hammocks were tiered three high and the man on the uppermost one stared into a tangle of pipes immediately above his face. The men below had to contend with the indentation made by the bodies of the men above them, and each had to adjust his position to provide adequate clearance.

Each “hammock” was approximately two feet wide by six feet long, and was strung about two feet from the “hammock” above. These hammocks were tiered three high and the man on the uppermost one stared into a tangle of pipes immediately above his face. The men below had to contend with the indentation made by the bodies of the men above them, and each had to adjust his position to provide adequate clearance.